A forum this week in Hobart has heard how COVID-19 restrictions helped the cities of Melbourne and Sydney roll out new separated cycleways a lot quicker than planned and forged important new relationships with the state governments.

The Menzies Institute and Tasmanian Active Living Coalition put on the forum: Rethinking Transport for Recovery, Resilience and Health at the Moonah Arts Centre and online for others around Tasmania.

The health angles of active transport and COVID recovery were covered by Professor James Sallis who is a world-leading expert in the field and Associate Professor Verity Cleland who talked about recent research she’d conducted on how to get more people catching the bus more often.

Of interest for bike riders were the two presentations from Melbourne and Sydney.

Sydney’s pop-up cycleways

Fiona Campbell, the head of the City of Sydney’s active transport efforts zoomed into the meeting to talk about the challenges and successes of being able to install pop-up cycleways during the pandemic restrictions.

These were already being implemented in other cities around the world as an alternative to essential workers having to use public transport, and were recognised as being useful in Australia for the same reasons

Pop-up cycleways generally use the existing road space, replacing parking or a travel lane with a bike lane separated by removable bollards and/or kerbing.

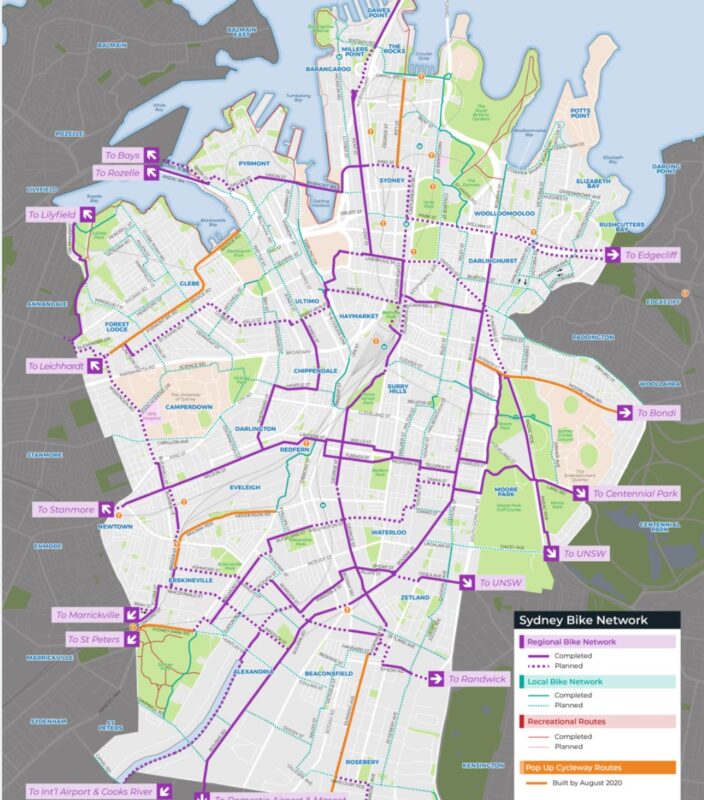

The City of Sydney worked with the state government to identify routes that had missing links in them that could be filled by the pop-up cycleways. Routes that led to hospitals, supermarkets and other essential workplaces were prioritised.

They were able to quickly identify the routes as the city had a cycling strategy in place that had already identified cycleways to be built over coming years.

The two levels of government decided on 6 pop-up cycleways, with the city building 3 and the state government 3.

They were all opened in July of 2020, within 5 months of the initial lockdown starting.

This was a big turnaround for projects that typically took years to go from start to finish but were expedited by the COVID-19 emergency approval powers in place and Transport for NSW fast-tracking changes to traffic signals.

They faced a few challenges along the way, the first being a shortage of supplies, but the long-term benefit of that was it forced them to look around for alternatives and now they have more options for future projects.

The other major challenge was the short timeframe for consultation, although they did have the flexibility to make adjustments along the way.

Because Sydney Cycleways has years of experience in rolling out infrastructure it also knew behaviour change programs were important so it spent 10% of the budget on rider tuition sessions, providing a buddy to ride with the person to their workplace, and bike maintenance and tune-up sessions.

Results proved project’s success

The goal of the pop-ups was to increase ridership by 10% on the selected routes, which was achieved on all cycleways, although the Pitt Street route saw a whopping 500% increase.

Interestingly, surveys showed that some 30% of riders would have driven a car if the pop-ups hadn’t been installed.

Other indicators of success were more women riding and feeling comfortable about it, and some 90% of people surveyed saying they felt safer riding in the pop-ups.

While there are some issues with the cycleways in terms of route choice and loss of parking, surveys of the general community found 71% support for the cycleways.

Melbourne fast-tracks its bike lanes

Luke Poland and Oscar Hayes were tasked with the objective of fast-tracking the City of Melbourne’s cycleway rollout just before COVID-19 hit.

Melbourne approved a Transport Strategy to 2030 in late 2019 that recommended 90 km of protected lanes be installed over ten years. Then in early 2020 the city declared a climate emergency and decided to fast-track 44 km of the 90 km target over 4 years.

The impact of COVID-19 on people’s use of public transport further increased the need to fast track the bike lanes.

Before the decision in 2020 to fast-track the lanes there were only 6 km of on-road protected lanes in Melbourne. These lanes had taken 3–4 years to deliver from start to finish so they knew they had to change their approach to deliver 44 km quickly.

One of the key differences was to change the way the lanes were built. Instead of permanent concrete barriers they opted for a temporary barrier that they developed with local company ORCA Civil that is made of 30–60 recycled glass sourced from the municipality.

The benefit of these is that they are just bolted on to the road so can be installed quickly, and importantly moved if the design of the lane proves problematic once it’s operating.

These were used to separate existing painted lanes and where they could they took them right up to the intersection instead of stopping it short.

The other change in approach was around consultation. Instead of a lengthy public engagement period, the team installed the lanes and then dealt with concerns. The temporary nature of the barriers means they can quickly remodel the separation if it proves an issue for driveway access, turning sweeps etc.

Results still coming in

Because COVID-19 lockdowns have forever changed the way we work, it’s difficult to compare pre-COVID and post-COVID data.

Before 2020 around 1 in 5 vehicles entering the city centre were bicycles, it’s now sitting at about 1 in 4 and looking like being on track to get to 1 in 3 by 2030.

Melbourne’s city centre only has about 36% of offices back to pre-2020 levels but they have already reached 70% of AM peak number for bicycle riders. And on some routes like Queens Bridge the AM peak is at 186% of pre-COVID levels. The same route had pre- and post-lane surveys which showed 33% of riders used to think it was a safe route, compared to 83% of riders following the lane construction.

Both presentations talked of the need for strong political leadership for the projects to succeed, with complaints being inevitable as the projects involved changes to parking and traffic lanes.

Both lots of projects faced media and public criticism over reduced road space for people driving but public service and political leaders have held their ground.

This factor, along with strong relationships between both levels of government to deliver the projects, was crucial to getting the lanes in place.